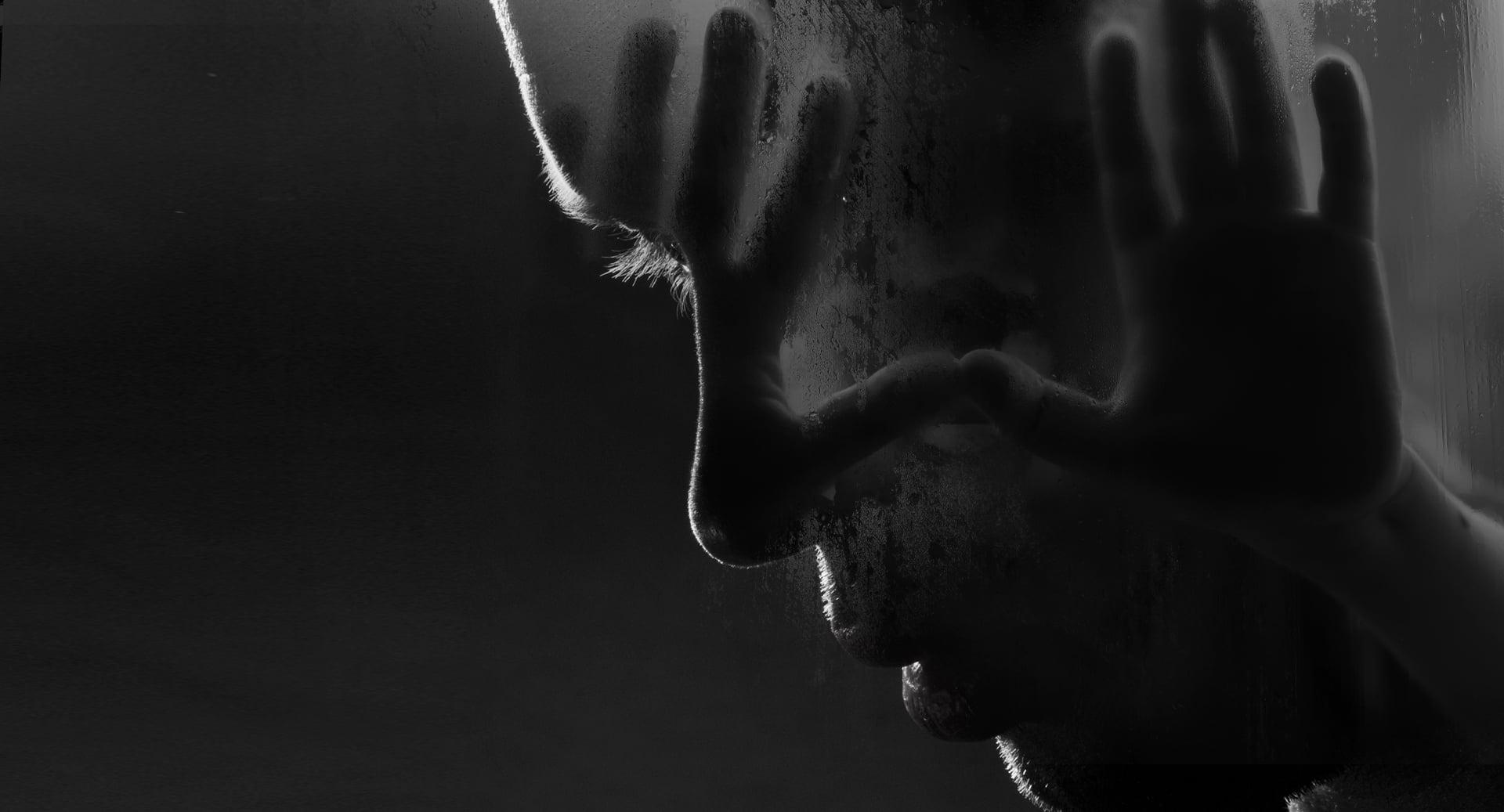

Dealing with Panic Attacks

Trembling, sweating or an impending sense of doom may signal a panic attack. But can we beat panic attacks? Clinical psychologist David Carbonell offers insights.

Panic attacks develop into agoraphobia when people feel so desperate to avoid future attacks that they begin to limit the activities they associate with a panic attack. For instance, a person who had a panic attack while waiting at a red light may try to avoid being stopped at a red light, perhaps while idling in the parking lane until the light changes. This doesn’t remove the fear, though. The fear will tend to grow, perhaps to the point where the person needs to avoid traffic lights entirely. And then, perhaps, noticing the similarity with four way stop signs, they begin to avoid those intersections as well. In severe cases, this person might stop driving altogether.

The more extensive the efforts a person makes to feel “safe” from a panic attack, the more extensive the avoidance becomes. Avoidance of multiple activities and situations due to fear of a panic attack is the heart of agoraphobia.

Because avoidance is the problem, exposure is the most effective treatment.

For a more detailed look at agoraphobia, see this article: https://www.anxietycoach.com/agoraphobia.html

Exposure is the key to recovery. If you panic when riding escalators, treatment will focus on experience with escalators in order to experience some panic, and have the chance to practice accepting and working with the panic symptoms, not suppressing or avoiding them. This helps a person, over time, gain confidence in their ability to feel the panic and move on.

Notice that the key element in exposure is exposure to the panic symptoms. So we don’t want to do exposure in which the client brings to bear all manner of anti-panic protections, such as: bringing a support person with you; the use of medications; the use of alcoholic beverages; distraction, and more. It's helpful to have a plan by which you'll work with the symptoms, but not to suppress or avoid them.

If a client tells me they did some exposure last week, and are happy to report that they didn’t panic, I might say “Don’t be discouraged – keep trying!” It sounds odd, but the key to recovery is practice with the panic symptoms.

Since relaxation training aims to get rid of the anxious symptoms, it typically wouldn’t be part of an exposure treatment, at least not a part that is used during or just before or after the exposure session.

For a more detailed explanation of exposure treatment, see this article: https://www.anxietycoach.com/exposuretherapy.html

Yes, but more commonly, these symptoms occur with other symptoms as well. It may well be that sometimes the symptoms of depersonalization/derealisation are so upsetting that a person fails to notice any other symptoms.

To read about people’s experience with depersonalization and derealisation, and some tips about responding to them, see this article: https://www.anxietycoach.com/depersonalization.html

This is actually an opportunity to make good progress, and it’s usually quite helpful when a client has a panic attack in session, because now we can observe and work with it directly. The client can observe the panic symptoms and their own instinctive reactions, can literally “catch themselves in the act” of opposing and resisting the panic in ways that usually make it worse rather than better, and practice the AWARE steps instead (link below).

Most of what I work with from CBT, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, is the “B” part, behavior. It’s helpful for people to relax their muscles, to change their breathing, to step into the panic rather than run away from it. I do less of the “C” part, because so often that part, the cognitive restructuring of anxious thoughts, leads people into an argument with their thoughts. Just because you can see the flaw or the illogic in your anxious thoughts doesn’t mean they will quickly go away. And they don’t have to! You can play with the thoughts and get much better results for your efforts.

By playing with the anxious thoughts, I mean humoring them rather than disagreeing: singing them; making a poem from the anxious thoughts; repeating them in a bad foreign accent; exaggerating and making the thoughts even worse, among others. It’s not necessary to change the content of the thoughts. What you need is to help the client change the way they relate to the thoughts. The anxious thoughts of a panic attack are not some accurate prediction of what's about to happen. They're simply symptoms of panic expressed as thoughts rather than physical sensations of emotions. All they mean is that you're afraid, and that's uncomfortable, but its okay to feel afraid.

I have a few panic attack songs I’ve offered to clients over the years. You can hear two of them (be forewarned, I’m no singer!”) here: https://www.anxietycoach.com/anxiety-humor.html

And here is the link to the AWARE steps: https://www.anxietycoach.com/overcoming-panic-attacks.html

It’s extremely rare to faint during a panic attack. In thirty years of practice, I’ve worked with about half a dozen clients who actually fainted during panic attacks. On the other hand, almost all of my clients feared fainting during panic without ever fainting.

Fainting is caused, not by fear, but by a significant reduction in blood pressure. Typically one’s blood pressure goes up slightly during a panic attack, which is why fainting during one is so rare. Those six clients who did faint had some other medical condition which overcame this natural increase in blood pressure and instead drove their blood pressure lower. Most of them had POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome).

If you’ve had years of panic attacks, along with fear of fainting, and haven’t had any actual fainting episodes (I know, everyone feels they “came so close”, but I mean actual loss of consciousness!), I would take that to mean you have panic disorder without any other condition which might precipitate fainting. In other words, you’re among the vast majority of panic sufferers who won’t faint during a panic attack. That doesn’t mean you won’t have fearful thoughts of fainting, but you won’t faint unless something else causes it.

Your question excluded blood/injury/injection phobia. I will just mention that people with this condition do often faint when they see blood. Everyone’s blood pressure drops a little when they see blood. This is helpful and protective, because whenever you see blood, there’s always a chance it’s yours. If that blood is yours, lowered blood pressure will enable faster clotting and less loss of blood. People with this condition just have too much of a good thing. When they see blood (or anticipate an injection) their blood pressure drops enough to cause fainting. For treatment, they need to learn how to raise their blood pressure in the situations where they expect to see blood or get an injection of some kind.

For more discussion of what people fear about panic attacks, and what the attacks can and can't do to you, see this article: https://www.anxietycoach.com/what-panic-attacks-can-do-to-you.html

The core of panic disorder is repeatedly fearing an outcome, like death or insanity, which isn’t produced by a panic attack. The sensations all represent discomfort, but panic tricks you into treating it like danger.

With respect to the fear of vomiting, my experience has been that actual vomiting is quite rare. However, when it has occurred, I assist a client to take some backup steps. For instance, airlines routinely provide vomit bags in the event of a passenger who vomits. I encourage a client with an actual history of vomiting during a panic attack to do something similar. But note that I only do this when there is an actual history of vomiting – not simply “coming close”, or thinking it was narrowly avoided.

People with emetophobia, the chronic fear of vomiting, rarely vomit. It’s a problem of chronic anticipation, avoidance, and unhelpful protection.

For a more detailed discussion of emetophobia, see this article: https://www.anxietycoach.com/emetophobia.html

For a discussion of how panic attacks trick you, see this article: https://www.anxietycoach.com/anxietyattacks.html

People may sometimes mistake a variety of conditions – low blood sugar, asthma, mitral valve prolapse, and more – for a panic attack. The first step, of course, after the onset of panic attacks is to be evaluated by a physician to rule out, or diagnose, any other potential causes of the symptoms.

People who have other conditions in addition to panic disorder may take a little while to learn to make the distinction. Generally as they experience the other medical condition, and become more familiar with its symptoms and pattern, they become better able to distinguish those from panic.

The concern people often have is that they don’t want to dismiss as panic some symptoms which may indicate something more dangerous. When I work with someone who has both panic disorder and some other condition which is potentially dangerous, and they have trouble telling the difference, I suggest they start by treating the symptoms as if they were part of the dangerous condition. So, in the case of a person with both panic disorder and asthma who has trouble differentiating them, I suggest the person respond with the asthma interventions which have been prescribed, such as an inhaler, until they get better at differentiating the two.

On the other hand, someone with panic disorder who has received a physical workup which does not find any other contributing cause may still experience “what if?” thoughts about having another ailment. Such thoughts are best treated as anxious thoughts rather than diagnostic signs. One physical workup is generally enough!

There is so much variety among the symptoms that are sometimes experienced as part of a panic attack that I rarely say no, a particular symptom would never be part of a panic attack. However, I am not aware of anyone experiencing the repetitive pattern of severe abdominal symptoms you describe as related to a panic attack. I would look elsewhere for an explanation.

Sounds like you're her therapist, yes?

This might be a good opportunity for you to “side coach” her while she’s experiencing a panic attack in the moment. You could communicate with her by private message in Zoom, or she could turn off her microphone and speak with you on her cell phone, or use e-mail or texting, depending on your concerns for security.

You’d want to first work out a plan with her as to how she might respond to a panic attack. I think this would involve her use of the AWARE steps (link below) and a good breathing exercise. You could also acquaint her ahead of time with the questions you’ll want to ask, questions similar to what appears in the panic questionnaire.

Links for these three items are below.

It would be good to have a practice session ahead of time, what I think of as a dress rehearsal or a fire drill, in which she runs through the steps she’ll take when she’s having a panic attack. That way, when the time comes, you can remind her what she did during the practice.

You’ll also want to work specifically with what she fears will happen if/when she has a panic attack during the zoom session. This might involve the traditional fears of collapse/loss of control we see in panic disorder, or it might be more of social anxiety fears, i.e., people will think poorly of her. These evaluation fears are much harder to disconfirm in the moment, because they’re about what others may be thinking of her, and require a different approach than the fears of imminent death and collapse.

Of course it’s best practice for the therapist to refrain from providing reassurance that everything will be okay and that her fears won’t be realized. Better to remind her that it’s okay to be anxious and that she has a good plan to follow.

https://www.anxietycoach.com/overcoming-panic-attacks.html https://www.anxietycoach.com/breathingexercise.html https://www.anxietycoach.com/support-files/diary.pdf