Transgenerational Transmission of Trauma

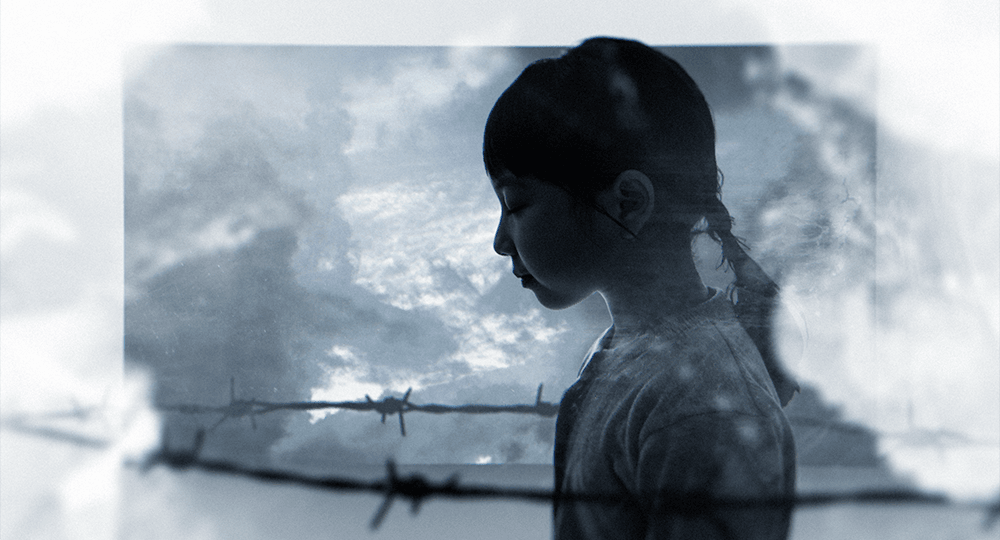

Research reveals that the biopsychosocial effects of trauma can be passed down across generations. Leading expert, André Maurício Monteiro, talks about mechanisms, markers, therapy, and more.

I first contacted the transgenerational transmission of trauma (TTT) in 1995 during a conference on group psychotherapy in Buenos Aires. I thought it seemed interesting at first, but the connection between the dates when current symptoms started and the dates of the birth/death of clients’ ancestors as a source of pathology seemed methodologically too far-fetched to me.

Fast forward to Edinburgh in 2014, I saw a presentation by Hélène Delucci on TTT at a European EMDR conference. The expression of pathology in the present being triggered by family secrets/traumas that could be reprocessed, if accessed, made more sense to me. The EMDR theoretical Adaptive Information Processing model (AIP) proposes that current symptoms and complaints stem from previous adversities that were not fully processed and are dysfunctionally stored in the brain.

The challenge of the EMDR clinician, therefore, lies in how to access this dysfunctional information that was experienced in the past – not during the adolescence or childhood of the client but lived through by an ancestor. Vestiges of these experiences mobilize our clients.

Certain common themes I have encountered in my clinical practice include irrational fears, such as the fear of starvation, homelessness, being murdered and so on, that do not match the reality of clients. Upon closer inspection with the use of a genogram, for instance, we may find indelible traces of family members having been previously exposed to war, persecution, migration, incarceration, hunger and generalized scarcity.

The expansion of AIP from an individual perspective that encompasses family history, allied with a series of protocols to help evoke systemic information has been part of my work, both with clients and EMDR clinicians.

The transgenerational transmission of trauma (TTT) should be counterbalanced with the transgenerational transmission of resources (TTR), a set of information transmitted to family descendants to promote survival and adaptation to an ever-changing environment. Both concepts can be integrated as TTTR, which includes the many different dimensions a traumatic event reverberates in individuals or groups that did not go through the experience first-hand. These consequences have been supported by various studies, such as the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE studies), where the mere witnessing of adversity is enough to cause emotional and physical imbalance in adults. TTTR creates a contextual frame where individual, family, social and cultural heritage links “foreparents” to descendants.

Systematic investigation of TTT began with the study of second-generation Holocaust survivors and their higher propensity for PTSD, despite not being directly exposed to concentration camp internment. The idea of TTT is implicit in every deeper clinical work, as therapists and clients attempt to investigate possible roots of present emotional discomfort, even when not systematically structured.

Intergenerational transmission pertains to the direct exchange from one generation to the next. One such example would be the study of insecure attachment styles. Mothers who exhibit an insecure attachment style serve as a template for a repetition of insecure attachment. Transgenerational transmission, on the other hand, involves skipping at least one generation. It is methodologically easier to observe direct parent-child interaction and its intergenerational consequences, as compared to observing the implications of exchanges between traumata suffered by a certain individual and the impact on their (grand)grandchildren.

Information, especially of a traumatic nature, finds various ways to move from one generation to the next. In some families, the traumatic past is in plain view and everyone is aware of it, sometimes even worshipping through rituals and storytelling. More commonly though, families cultivate silences surrounding certain themes or family members one should not dare to address. The absence of an official narrative may play an important role in signaling genogram hotspots. The pathogenic power of missing narratives may be depicted by a man whose discomfort regarding tattoos was traced back to the numbers tattooed on grandma’s forearm – and her disclosure of having been a concentration camp prisoner only when her grandson had reached his thirties.

Deficient integrative capacity is another significant recurrent mechanism for the transgenerational transmission of trauma. A client only realized the dread she had of taking care of people/pets/plants was related to a family tragedy when grandpa scared grandma, who was close to the stove, somehow leading to a pan of boiling water spilling over their daughter (the client’s aunt) and killing her. The client “knew” about the tragedy, but had never connected the dots between her current incapacity to have anyone depending on her and the fatality from the past. Through EMDR, she managed to reprocess the image of the kitchen accident in her mind and forgive the grandfather she met briefly in childhood as he was dying from cancer.

Another client knew her father and grandfather had been war veterans (both suffered from PTSD, alcoholism and depression), but had never connected their outbursts of fury to her helplessness whenever her daughter threw a tantrum. Daddy losing his temper and her daughter’s occasional defiance made her feel helpless to deal with confrontation. The information is often present, but not processed in a way that allows for associations within memory networks.

All of our body cells contain the same genetic information. However, a neuron is very different from a blood or skin cell. This means that genetic information is expressed differently: certain attributes are expressed, while others remain silent. Does this happen only in physical terms, or do experiences and intense emotional states also shape our hormonal, immunological and behavioral expression? This is the growing field of epigenetics – the study of how gene expression is enhanced or hindered. What about behavioral epigenetics? Apparently, certain experiences that our parents and grandparents were exposed to in childhood alter the expression of emotions and behaviors in their descendants.

There is plenty to be researched and countless variables to be considered. Scientists research, for instance, how the womb environment impacts the genetic expression of the fetus and subsequent generations. A classic example is the Dutch Hunger Winter study, which followed the descendants of women who underwent acute malnourishment during their pregnancies at the end of WWII. These people suffered from permanent changes that affected their physiology and that of their offspring. The ways emotional chronic states, such as relentless anxiety and depression, influence descendants remain to be further researched.

Narratives create realities. An adult who suffered humiliation through bullying as a child may feel ashamed and develop a negative cognition: “I am fragile.” Through reprocessing, the same adult may regard this experience through different lenses, such as someone who learned how to withstand pressure and come to view the same experience with a positive cognition: “I am persistent.”

Family storytelling may select emblems to convey values across generations. A client may feel it is impossible to get a university degree because the family values humility as a virtue. It would be disloyal and arrogant to infringe on this unspoken rule. Reprocessing blocking beliefs may help clients to rephrase narratives and adjust inflexible warnings from the past into newer, more adaptive paradigms: “I may succeed (and that is no offense to my ancestors).”

Since transgenerational trauma is essentially a trauma-based perspective, EMDR therapy has helped me promote healing and access to the transgenerational transmission of resources within families. Certain therapeutic approaches rely on the realization that the past interferes with the present, such as psychodynamic therapy and Gestalt. Realizing trauma, however, does not guarantee reprocessing. Insufficiently processed traumatic experiences may be understood at a cognitive level, but the disturbance remains in the felt sense. The actual transmutation of the experience into a narrative that reorganizes the distinction between past and present requires a comprehensive intervention of the thinking dimension, coupled with emotional/somatic components. My former training in psychodrama has also been useful at times, through the articulation of cognitive knowledge, emotion, physical sensation and action.

Whenever clients come to therapy with clearly defined complaints, such as fears and traumatic memories, therapists may focus on these memory targets and reprocess the maladaptive information with just a little stabilization. However, clients who display signs of dissociation usually require additional self-regulatory skills to better navigate the traumatic landscape, maintaining themselves within the window of tolerance. Moving beyond these presentations, we may also come across clients who may or may not dissociate, but present complaints that do not accurately match their present situations, such as irrational fears, impulses, emotions and physical sensations which indicate that memory components are more fragmented and may not provide an accurate comprehension of their discomfort.

A civil servant with a steady governmental career mentions in therapy that the drawers at her office desk are always full of chocolates and sweets. At home, her fridge and cupboards are always packed with food. She complains of a constant sense of emptiness and impending doom. She can reach a supermarket just a few yards from her apartment. As we float back in time, through her scanning her past, she remembers a story her mom once told her about grandma sewing jewels inside her sweater in WWII so she could eventually exchange them for food. The story had not impressed her at the time, but now the account brings new light to her eyes. We reprocess the image she has of grandma sewing her coat and anxiety levels decrease. Transgenerational transmission of trauma (TTT) complaints are often subtle in nature. Some of them are not even worth mentioning in therapy, but with an everlasting presence in one’s life, uneasiness is regarded as a normal companion.

TTT information may also manifest itself through family sayings. “As grandpa used to say, birds of a feather flock together.” What does that mean and how may that message be adjusted to an individual's self-concept? TTT presentations tend to be elusive and do not usually show up at the beginning of therapy. They may be referred to almost by accident as something not therapy-worthy, just a passing thought to be shared – but with unsuspected ramifications in the lives of clients.

Transgenerational traumas were not witnessed by the client but apprehended indirectly – like a message in a bottle, thrown into the oceans of time. What we, as EMDR therapists, usually focus on are auditory accounts or silences involving certain themes hidden in plain view, inconspicuous family members, or unremarkable observations that characterize dysfunctional information being stored in the brain.

Once the client manages to make the connection between the current disturbance and the recollection (usually visualized by the client as a vivid image, old family myth, or uncertain report from the past – despite one’s absence at the original traumatic scene), reprocessing tends to be almost spontaneous. Our challenge, therefore, is to devise strategies (protocols) that help clients access this camouflaged information.

Though subtle, these stories, collective values, family sayings and tunes are pervasive enough to slightly modify the functioning of Adaptive Information Processing – the lens through which clients perceive the present, create obstacles, disrupt motivated behavior, procrastinate and deform decision-making processes, impede life plans and blur the ability to enjoy love and live. Once these are accessed and reprocessed, an important follow-up task is to help clients integrate these results of getting disentangled from the past into the new routine.

Though trauma may have been collective within the family, or even societal in nature, our clients’ perspectives remain individualized and tailor-made. Through a more relational approach, therapists can help clients update their legacies and integrate what was granted to them by their ancestors as lessons to be learned from, instead of relived.

Investigative protocols, such as the exploration of family sayings and the genogram in Phase 1 of the standard protocol (history taking), have been devised to promote the linkage between family history/social framework and the individual presentation of problems. The main initial question remains related to the principle of floatback and body scan questions:

Where may this problem have come from? When did you learn this?

Is there anyone else in the family who might be suffering/may have suffered what you are going through?

Is there a story you heard in the family that might be related to what you are going through and what others may have also experienced?

As mental health communities become more trauma-informed, emphasis may be placed on the:

Preservation of clients’ interpersonal neurobiology, as the brain is considered a social organ

Principle of integrating our historical heritage

Possibility of expanding EMDR through group work

Many EMDR therapists have been devoting their time and expertise to alleviate suffering at community levels through early intervention group protocols, especially in post-catastrophe contexts. The post-COVID era has enabled us to virtually go worldwide and access many people in need; something we would not be able to accomplish otherwise just a few years ago. The mental health landscape has been changing significantly in the last few years.

A wider awareness of group relations and the transgenerational transmission of information, whether through unresolved trauma or resilience and post-traumatic growth, paired with psychoeducation on mental health preservation, can serve as the basis for institutional programs. These programs can aim to address the complexities of transgenerational trauma and therapeutic strategies for healing. EMDR therapy may become a forefront vehicle for that purpose.