Understanding Motivational Interviewing

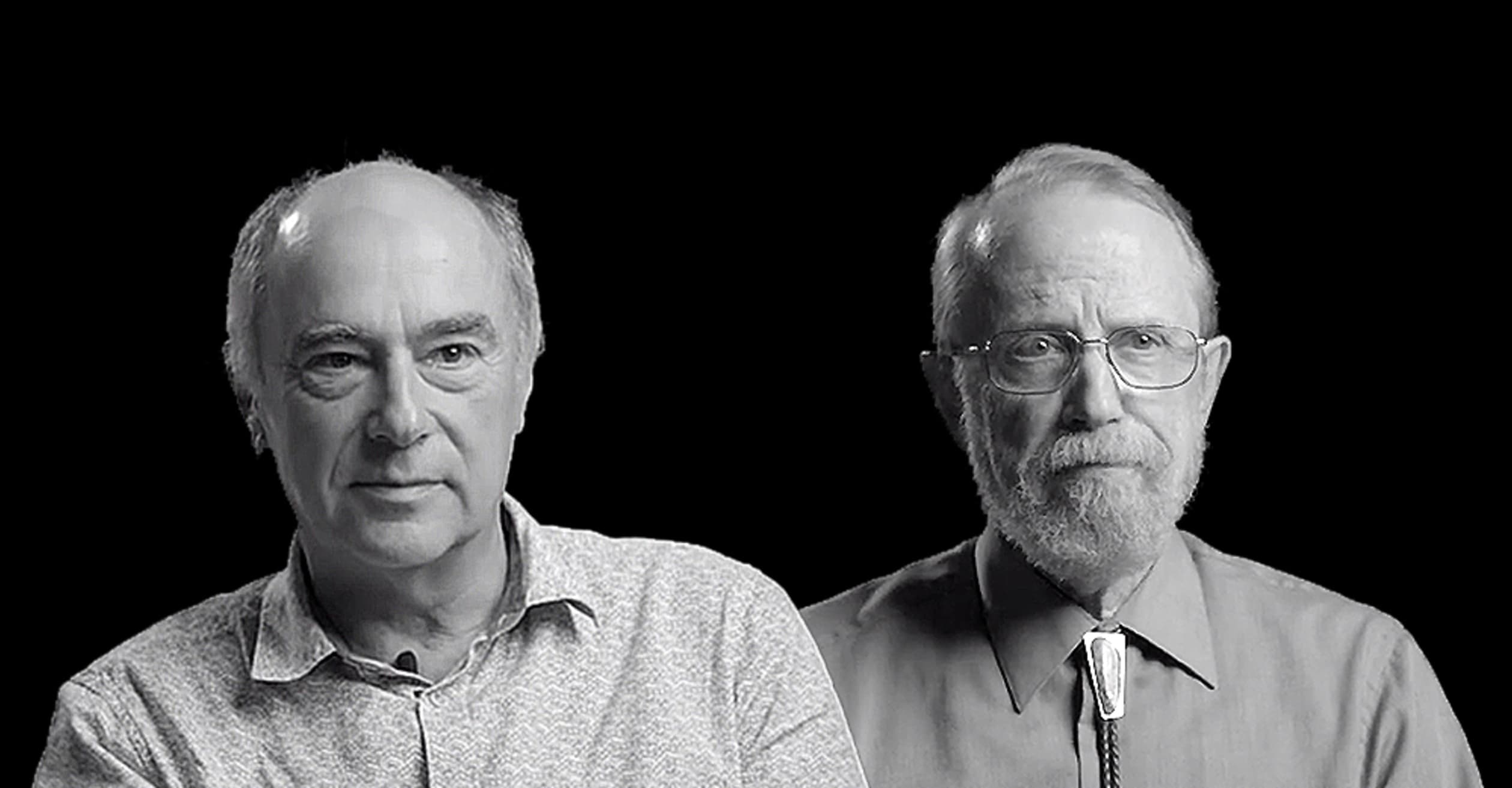

William Miller and Stephen Rollnick cover the ins and outs of Motivational Interviewing, a client-centered approach to behavior change.

My hope is that the implementation of MI will help to humanize health care and strengthen patient-centered medicine. So much of health care addresses chronic illness, lifestyle diseases directly related to patients' behavior. In acute care medicine we can fix things - broken bones, infections, wounds - but when it comes to helping patients change their behavior and lifestyle, medical training often provides little preparation. MI can be used in the context of brief health care visits. Even better, I think, is to co-locate behavioral health providers in primary care settings, allowing in-session consults, integrated care, and a warm hand-off with a short walk down the hall. Health behavior is very changeable, and is one of the primary determinants of the course of chronic health problems.

Interesting question, and I hope I understand your meaning. Patient autonomy is a fact, and not something we can "give" to people. Explicitly acknowledging and honoring autonomy can diminish defensiveness, and it is always a background assumption in MI that people get to make their own choices. Because what we are eliciting as change talk is the person's own motivations for and ideas about change, I don't see a conflict with patient autonomy. Knowing that people make their own choices can lift from the practitioner the burden of imagining that we have to make people change.

Definitely not. MI and the transtheoretical model grew up together in the early 1980s, and they make sense together, but we don't fret over what stage a person is in, partly because it can change so quickly (in either direction) over the course of an interview. We try to stay with people wherever they are, and I think that an MI style can be helpful at any stage of change. The four processes in our 3rd edition can also be helpful here. If somebody seems to be ready for change, I wouldn't spent a lot of time evoking. If there is already a clear focus, take some time to engage, but the primary task would be planning, and evoking commitment to a provisional plan. The processes are flexible, not linear.

No no no! While the stages model is a useful background framework, I would rather allow people to shift in and out of different stages as a conversation unfolds!

That is the main focus of chapter 16 in our 3rd edition: Evoking Hope and Confidence. It certainly happens that people see change as important, but they experience little confidence or self-efficacy for making the change. That is one of Steve Rollnick's important contributions to MI. There are some familiar strategies, such as reviewing past successful changes. Interviewing people about and affirming their strengths is another, which is a purpose of the "Characteristics of Successful Changers" tool. Evoking, reflecting, affirming, and summarizing ability language (one kind of change talk) is a mainstream strategy in MI. It is also worth noting that sometimes people are reluctant to acknowledge the importance of change until they see that it's possible. If you increase someone's perceived importance of change without also evoking hope, you haven't done them a favor.

I don't want to sound strange, but ask the client? I say this because while there's lots of guidance and wisdom in the view of experts, and I agree with what Bill says above, there's wisdom in the client too. Asking the client also relieves you from the burden of having to be clever and find the answer? Celeverness never did me any good! I got on top of MI when I consciously tried to let go of my cleverness, so that my mind was clear and focused on the client's needs. In one sense, the client is our best teacher. Just one way of looking at it. The challenge here is all but universal in settings of poverty, where economic and social conditions render people much less able to control outcomes in their lives, so no wonder they don't feel confident. So its not just some psychological challenge, yes? Important to acknowledge this dont you agree?

Again, patient autonomy is a fact. We can acknowledge it or ignore it, but people can and do make their own choices. When someone walks through the door of a smoking cessation clinic or an addiction treatment center, it's no secret what the providers' goals are. The question is: how shall we interact with autonomous people as caregivers? If we pretend that people don't have autonomy, we can take on a prescriptive expert role: You have to . . . You must . . . Do this, do that. The normal expected outcome is no change, and then we blame people for not changing and "resisting." When what needs to change is a client's behavior or lifestyle, we need their collaboration and expertise.

That tension is for real. Imagine a heroine-addicted client who is making a living through prostitution and also loves her daughter. The tension is there for sure. But I wouldn't feel the need to disguise advice. I would work damn hard at engaging, and then ask permission to give advice, and then try to highlight choice and autonomy, and listen hard to her sense-making, often including change talk. If I am genuine and sincere, guided by compassion, then I can respect her choices.

Ambivalence is not limited to the contemplation stage. It continues as people seek to maintain long-term changes in behavior and lifestyle. Part of this is a way of thinking. In the addiction field we have clung to the concept of "relapse" which essentially says that there are only two possible outcomes: perfection or disaster. In fact, most treatment outcomes in substance use treatment lie somewhere in between perfect abstinence and persistent dependent use. We don't use perfection models in addressing chronic illnesses like diabetes or cardiovascular disease. If patients come back in hyperglycemia or hypertension, we don't say, "You relapsed!" Rather, we set about the business of figuring out what needs to change to help the person regain and retain health. So yes, MI can be useful in helping people get back on track and maintain long-term change.

I love Bill's answer, and cant add much more to it! Perhaps this: we have expanded the view of MI to embrace conversations about goal setting and planning. Eliciting the person's own motivation and good ideas about how to maintain change despite setbacks is certainly within the compass of MI.

In addiction treatment, the field in which I worked for most of my career, risk is always involved. "Nonjudgmental" is about how we treat the person, rather than the problem. Carl Rogers described it as unconditional positive regard - that the client does not need to earn our respect or compassion. It's more than attitude - it's specific clinician responses. Lecturing, scolding, labeling, shaming, and such are judgmental responses, and are unlikely to inspire change. Acceptance, ironically, facilitates change. Rogers described the paradox: when we feel unacceptable, it is paralyzing and makes it difficult to change. In experience acceptance as we are, it becomes possible to change.

That's a nice distinction Bill made between the person and the behaviour or its consequences. Yes you also want to be authentic in the conversation, and if you have concerns about risk you also want to be authentic and address them. Two vehicles come to mind: first, a solid platform of engagement, and secondly, asking permission to share your concerns about risk to the client or to others.

I have been saying that MI is a way of doing what else you do. Whatever treatment for depression you may provide, be it cognitive therapy, behavioral activation, or pharmacotherapy, it matters HOW you provide it, your way of being with the client. MI is not an alternative to evidence-based treatments for depression. It is a way of delivering them. Often treatment for depression involves helping people to DO something different - exercise, engage in pleasant activities, change thinking, take medication - even though they may not feel like it. That is a clear example of ambivalence that can be addressed by MI.

I am worried about expert judgment here! This field of "evidence-based treatment" and the striking elevation of CBT (and its relatives) over 30+ years sometimes feels like a competition between therapies. So I dont want to replicate that kind of judgment about which therapy helps with depression. I suspect that for most practitioners the conversations with people who are depressed have more in common than differences. Where are the accounts of what MI looks like with people feeling depressed? I hear colleagues, in primary healthcare for example, say that they find MI very useful when talking to people who experience low mood. Bill's observation about ambivalence is striking and valid in my experience. Whatever approach you take to depression, surely you will want to establish good engagement, and draw out the client's own good sense of why and how they might change? That's the way I see MI in practice.

Applications of MI In activism have been appearing to encourage pro-social behaviors about which we may feel ambivalent, like blood donation and recycling. The person-centered approach on which MI is founded has long been used to promote communication that counteracts racism and political divides. I'm clear that empathic listening is important in healing such divides. Whether what we have learned in addition in MI will be helpful remains to be seen.

This is a really tricky question, although I am not sure what "used empirically" means. if by that you mean used, studied and found to be effective then I doubt it. Can a conversation take place about littering or racism that is less confrontational, involves empathic listening and someone pointing the conversation towards a change in attitude and behaviour? I would say so. Imagine a teacher sitting down with a student who expresses racist views. I can see Mi being incredibly useful. So too I can imagine a sports coach talking with a young athlete about littering and MI being much more effective than scolding or confronting the young person. The conversations happen about these topics, and if Mi can inform better outcomes then perhaps we should help to empower teachers and even parents to develop their skills? That's a quite radical suggestion and I acknowledge that there is no empirical support for it.

Simple answer: No. It's a lack of well-designed clinical trials, so we just don't have a credible answer yet. What we do know so far is well summarized by Stinson and Clark in Motivational Interviewing with Offenders: Engagement, Rehabilitation, and Reentry.

The best way to know is from how your clients respond. In a way, a reflection is a summary. I have not been above interrupting clients to offer a reflection. "Hold on a minute. Let me make sure I understand what you're saying." Particularly if a client is saying the same thing over and over, it can be because they don't feel heard or understood. Clients are giving you immediate feedback about your practice. If you're hearing change talk more than sustain talk, you're probably on track.

Clearly yes. There are clinical trials of MI in group settings. The Wagner and Ingersoll book on Motivational Interviewing in Groups contains good guidance. I don't know of any trials directly comparing individual versus group MI, so it's hard to say that one is more effective than the other. I usually recommend honing your MI skills first with individual sessions, because in groups you are also managing group dynamics and each client gets less air time.

Here is what I said in response to a similar question: There isn't enough research to say with confidence. I suspect that there is a level of cognitive development and executive self-regulation that children need to reach before they might respond as direct recipients of MI. It's clear that MI can work well at 16, 17, 18 and up. In fact, some of the biggest effect sizes we saw in our own research group were in working with adolescents. The engaging skills of MI - good listening - can be useful at any age. Thomas Gordon was describing Carl Rogers' discoveries in his 1970 book Parent Effectiveness Training. We just don't know at what age the evoking/directional components of MI can be effective. I guess the saving grace is that with younger children, you really ought to be working with the parents anyhow. Until children reach a certain age, the parents ARE the executive control system.

Now there is a terrific population with whom to practice MI. You are beautifully describing ambivalence - they know what they need to do to be healthier, and they are also comfortable with life as usual. I got a first hand exposure to that when I was diagnosed with adult onset diabetes. I was sent to a diabetes educator who provided a 90-minute download of information and advice, and I sat there thinking, "I believe I know a better way to do this." 90% of people with diabetes are not on target with all three key indicators - glucose (A1C), blood pressure, and lipids. These are lifestyle diseases, and lifestyle is changeable, but not likely to respond to warning, lecturing, and prescriptive advice. Lifestyle is exactly where MI began. With a diabetologist I published Motivational Interviewing in Diabetes Care. There is the Clifford and Curtis book, Motivational Interviewing in Nutrition and Fitness. Steve has written extensively on motivational interviewing in health care. There is a sizable clinical trial literature with mixed but encouraging results. All I can say is, try it! Often providers see relatively quick changes in how their patients respond when the switch from directing to guiding.

Steve may tell you a story of a physician who told him, "I couldn't see that many patients in a day if I didn't practice MI." But MI is not a solution to overwhelming job expectations. Practicing MI and empathic listening is tiring! When you see person after person all day long with complex and heart-rending situations, it does take a toll, and self-care becomes vital. Health care workers in the era of coronavirus are already facing overwhelming odds. I would ask you what you already know about yourself and your work, and what is needed. Our ability to help is now limitless.

That's a very humbling question. I know the experience. Indeed, looking back, I started burning out in clinical practice after 15+ years.... and I wish I had your humility in those days, to call for answers to that feeling of tiredness and overwhelming complexity in the problems that showered over me every day! Without a sense of calm and relative wellbeing within us, we can practice well, whether it is MI or not. So I would look not at my clinical work but how to settle myself, look after my own wellbeing, and take it from there? You are not alone, that's for sure. I wish you well.

Not to my knowledge and I don't think it's likely to be a stand-alone treatment. There have been some clinical descriptions of MI in suicide prevention, but not clinical trials. MI is not an alternative to other evidence-based treatment methods, but a way of delivering them. In discussions with Marsha Linehan and Judy Beck, MI is very similar to the clinical style they use in providing DBT or CBT, respectively.

I doubt that research has been done on MI with adolescents in trouble with self-harm and potential suicide. Although not unique to Mi as such, listening without judgment is a powerful ally. However, Mi has a more purposeful quality, and I would sooner look to read about these subjects beyond the MI field .....

Whether someone in a domestic violence situation should leave the relationship is, in my view, a moral choice in which I would ordinarily counsel with neutrality (Chapter 17 in our 3rd edition), although "Get out!!" can be a powerful righting reflex. Safety is a prime directive, and MI is beginning to be used by social workers in child protective services. It can be practiced with offender or victim, or both. There is not much scientific research thus far on the efficacy of MI alone in such situations, and I wouldn't use it alone. MI is a way of doing what else you do, a way of being with the people you serve.

How and why MI might be used in domestic violence is a really tricky question. If safety is the main concern, then MI seems relevant. However, practitioners are usually well aware of the need to help victims to make up the minds for themselves, and MI is usually used with a specific goal in mind.

In two multisite trials of treatment for alcohol use disorders (Project MATCH and the COMBINE trial), the manual urged clinicians to include a significant other in at least early treatment sessions, and MI was the prescribed clinical style. In those studies, the partner was engaged to help the primary client make specific changes. In couples counseling more generally I found it helpful to identify the relationship as my client, rather than one partner or the other. A challenge in doing MI with a couple is that while you're doing your best to listen well, the partner may jump in with communications that evoke sustain talk and discord, so you have to manage that. One approach is to teach the couple the very communication skills that you are practicing, particularly the engaging/listening skills.

We do know that the quality of MI being delivered matters. "People cannot benefit from a treatment to which they have not been exposed." There are more providers who believe they are doing MI, than actually are. That was a hard lesson the first time I evaluated my own training workshop with pre- and post-training practice tapes. I got rave reviews, and participants told me how much they loved MI and were using it in their practice. If I had stopped with the post-training questionnaires, the workshop appeared to be a smashing success. On the post-training practice tapes, however, there was very little evidence that I had been there. They offered a few more reflections, but their clients' in-session responses (which predict outcome) changed not at all. They were convinced they were now practicing MI, and were less interested in learning more because "We already learned it." That wasn't their fault, it was mine. I had been implicitly thinking that at the end of the workshop they would have it. That began a long series of studies on what it actually takes to develop competence in MI. It turns out that even a modest amount of feedback and coaching based on observed practice can make a large difference in learning and the maintenance of gains - just like any other complex skill.

There can be organizational barriers to providing good MI - requirements and an atmosphere that contradict the underlying spirit of MI. After one of our subsequent training studies, we found at follow-up that some of our trainees had left their place of work. "Having learned MI, I couldn't work there anymore."

I smile, having raised three adopted children. The engaging/listening skills are super useful, as Thomas Gordon described in Parent Effectiveness Training (1970). I refrain from the evoking/directional aspects of MI with my own kids (let alone my spouse), because I am not sufficiently detached from their outcomes. Yet what we have learned in MI does suggest what NOT to do, which is getting locked in win-lose scenarios. While raising children I used everything that I had ever learned, and it still wasn't enough, so I fall back to just loving them.

I smile, having raised four kids and spent a lot of time with their friends. How about this for a question? What is the aim of MI? if it to promote change in someone's behaviour then I think it is of limited use at home because we are too invested in the outcome. However, what if you saw the aim of MI as to help someone grow and thrive? Then surely there is no emotional investment problem and MI can be used with a 2-yearold, or the underlying guiding style at least?

You surely know more about this than I do. Dr. Charles Bombardier at the University of Washington and Harborview Center in Seattle has experience and publications in applying MI with cognitively impaired and impulsive patients, particularly closed head injuries.

A name that Coes to mind id Dr David Manchester. I would read anything by him I can lay my hands on. Smart clinician with lots of experience. Based in Sydney Australia. I have no experience in your field. My only question would be about what the benefits are of working with peoples' strengths, not just their deficits - easy for me to say this form the outside! All best wishes.

We don't make suggestions on specific cases. It's a familiar scenario, though, to get locked into an adversarial struggle with the clinician providing solutions and the client saying why they won't work. First of all, it is entirely possible for clients not to want to make any changes. It's not a problem unless you are somehow expected to MAKE them change, which is impossible, by the way. We describe "coming alongside" as one approach that essentially agrees with the client that perhaps no change will be acceptable. "Smoking may be so important to you, that you need to continue no matter the consequences." It has a taste of paradoxical intention, but basically you're telling the truth that the client is telling you. Sometimes when you are no longer struggling to make the client change, things turn around.

I know this experience and definitely dont wish to offer suggestions about your client, someone I dont know at all. In the past I have found supervision to be helpful. I also find that stepping away from situation, with the client, has been useful. By this I mean certainly not trying to promote change, but also being open about the situation, saying how you feel, asking the client to do likewise, suggesting a break from counselling, or anything that encourages them to step back..... be honest and genuine about your feelings...... in the end a good supervisor has been my greatest form of support....

We don't provide advice on specific cases, but I have certainly done MI and seen it practiced with relatively silent clients, particularly teenagers. Questioning is not usually the way to go. So few adults listen to teenagers, that empathic listening in itself can be quite powerful. When we were filming demonstrations of MI, I was assigned to demonstrate reflective listening as a primary response. I had not met the client, and had no idea what scenario he would bring. Thirty seconds into the filming I'm thinking, "Great! I'm supposed to demonstrate empathic listening and I get a client who doesn't talk." Monosyllabic or short responses, long latency. It turned out well, however, and has endured on our training DVDs as a demonstration called "The Silent Man." Reflect what you see, the nonverbal messages, and make complex reflection guesses about whatever short replies you receive. Trust the process. If you're busy trying to think of clever questions to ask, you'll miss what's happening right in front of you.

It might be useful to look at literature on this subject, like the book by Dr Sylvie Naar. No progress can really be made without engaging first, and the use of reflection might be key here. Then I might consider more concrete activities in the conversation....

MI just keeps spreading into new cultures, languages, professions, and contexts. Clinical trials are appearing from African, Arabic, Asian, and Indian nations. When I wrote the first article in 1983 I certainly did not imagine applications in dentistry, education, corrections, social work, and leadership. We have learned so much more about change talk and how MI works. An interesting recent trend from meta-analyses is that diminished sustain talk can be a better predictor of outcome than increased change talk - in other words "softening sustain talk" seems to be particularly important. There are fewer clinical trials of MI as a separate stand-alone intervention, and more that combine MI with other evidence-based treatment methods. That's what happens in practice. I don't know anyone whose practice is limited to MI. If there is eventually a 4th edition of our book, we're not sure what it will contain, except Steve and I hope it will be simpler.

New directions in motivational interviewing will emerge wherever sincere efforts to encourage change and growth arise. By sincere I mean efforts that have a genuine focus on the interest and wellbeing of people. There will also be limits to where MI can or should be used. MI is merely a refinement of a naturally and widely used guiding style used by parents, teachers, sports coaches .....

There isn't enough research to say with confidence. I suspect that there is a level of cognitive development and executive self-regulation that children need to reach before they might respond as direct recipients of MI. It's clear that MI can work well at 16, 17, 18 and up. In fact, some of the biggest effect sizes we saw in our own research group were in working with adolescents. The engaging skills of MI - good listening - can be useful at any age. Thomas Gordon was describing Carl Rogers' discoveries in his 1970 book Parent Effectiveness Training. We just don't know at what age the evoking/directional components of MI can be effective. I guess the saving grace is that with younger children, you really ought to be working with the parents anyhow. Until children reach a certain age, the parents ARE the executive control system.

Ehm...... I am not sure. . Children are generally also more curious and imaginative than older people, and evoking is partly a process of encouraging people to imagine different outcomes..... so I suspect that with refinement MI could be used with younger children. With what effect I dont know. I know that at home if I use reflection with my 8 year-old it can evoke change talk? "So you want to go out into the park...." (Reflection) "Yes, then we can find those sticks and make a bow and arrow" (Change talk).

It is certainly easier to practice one-to-one, and I usually suggest developing your MI skills with one person at a time before starting to practice it in working with relationships, families, or groups. You are managing relationship or group dynamics in addition to practicing MI. Wagner and Ingersoll published a very helpful book on Motivational Interviewing in Groups, and outcome research shows it can also be effective in that context.

We know that MI works well with individuals. Not enough is known about the practice and effectiveness of MI in groups. The potential is there. What MI skills bring to bear on skillful group facilitation is an awareness of language, of avoiding the righting reflex and of how using reflection in a group is a powerful technique, a bit like patting a balloon back onto the group for them to pat about among themselves!

If I were still doing research myself, I would be trying to understand how learning and practicing MI changes practitioners themselves. Clinicians often tell us how their lives and work were changed in important ways through the practice of MI, but there has been no prospective research on this so far.

Good practice starts with ourselves. I would like to see more research on practitioner mindset and wellbeing. For example, how does empathy impact wellbeing, especially its use in a purposeful manner in MI? Perhaps it helps with wellbeing because its use is purposeful? However, with my very practical focus on patients appearing in tough social and personal circumstances, I would like to see the study in detail of the impact of the Elicit-Provide-Elicit framework for giving information and advice. This could really improve everyday practice.